A few months ago, Ayana (aka The Vintage Guidebook), and I connected on Instagram, and we began messaging. She asked me for information on how to go about researching re-creating historical clothing, and so I asked if we could co-author a blog post on it.

This is not a new subject in the enthusiast/hobbyist/amateur historical costuming world, but it never hurts to have a refresher, and maybe we can bring something new to the table. Later on I will try to link to other’s takes/resources on the topic.

I plan on breaking this series of posts down as follows, but with the freedom to mix it up as new questions arise:

- Part I: Where to Begin

- Some Misconceptions

- Where I Like to Begin

- Part II: Information Sources

- Categories of Sources

- Credibility of Sources

- Types of Sources by Era

- Part III: Recommended Sources

- Sources I Recommend

- Resources by Other Historical Costumers

- Part IV: The Academic Side of Things

- Academic Viewpoints on Historical Costuming

Some Misconceptions

- Sewing historical clothing is instant and perfect! I can make a whole outfit in a day!

This is patently untrue. Sewing historical clothing is one of those hobbies where the journey is just as important is, if not more important than, the outcome. It means you won’t get everything right on your first go at something. It also means that new research can render an old project not HA (short for “historically accurate” – look, now you know the lingo!). Furthermore, it means there is always more research to be done…oh darn 😉 Try not to worry about this too much, or you end up never starting anything. It is also OK to not be that interested in historical accuracy – if you are just having fun making “oldey-timey” outfits, then this maybe isn’t the blog post for you. However, someday you might found out on your costuming journey that the HA stuff becomes interesting to you. - Looking at pretty pictures!

Researching how to make historical clothing requires both visual and textual references (i.e. looking at pictures AND reading). If you can get to examine extant (meaning surviving) vintage and historical garments, that is also really helpful, even if it is just by visiting museum exhibitions. Please also remember that most of the remaining evidence has to do with wealthy, upper and middle-class fashions, which were generally made at the expense of/by exploiting people who didn’t have as much privilege or resources. - I made a thing – now I’m an expert!

After going back to school for my master’s, it became really apparent just how much misinformation there is floating out there on historic fashion/dress, even sometimes among academics. That isn’t to say someone who does this as a hobby, or at least not from an academic standpoint, can’t be really knowledgeable. It is just a word of caution at taking things as fact just because someone makes a lot of pretty outfits or has a lot of followers. Later I’ll get into what to look for to help decide if information given is credible or not. - I’m an expert – therefore everything I say is fact!

On the other hand, a “good expert” should acknowledge that fashion history, being part of the field of history, is an interpretive field that is highly nuanced. People try to generalize findings all the time, but the truth is, it is never going to 100% fit into a neat little timeline arranged by arbitrarily drawn borders on a map. The nuances are what make it exciting – fashion/dress history is as varied as every individual who ever chose to put (or not put) clothes on their body. - It is OK to start with “basic” garments…and it is OK to stick with “basic” garments.

Historic costuming, unless you do it for work at a museum, often has a deeply social aspect to it, both in the face-to-face world of events like Costume College as well as online on social media. It can be a world that feels clique-y and exclusive. It is easy to feel intimidated or that your pieces you make aren’t good enough because they aren’t the flounciest, have the most yardage, most trimmed and bedazzled, or even because they’re not the most HA, or because you can’t afford to travel to exotic locations to take photos of them.

I still sometimes feel inadequate because I don’t have a whole wardrobe of historic costumes yet, until I remind myself that this doesn’t make me a lesser person/costumer because of it. Because of my life and career path, I’ve just never had a lot of free time, or expendable cash for my hobbies. After all, I’m not in the socioeconomic upper class in the time period that I actually live in, so how can I expect to afford to make an upper class wardrobe (or several) from a different time period? Part of the reason we are able to do so now is because of automation of textile manufacture, but also because we are still exploiting those with less privilege and resources to have cheaper material goods on the market.

Personally, I’d love to see a more diverse representation of socioeconomic levels and cultures in the outfits at historic costumer events. I think it would help break up some of the clique-y-ness and make it a much more welcoming and accessible space, with richer discussions about the subject of fashion/dress history.

Where I Like to Begin

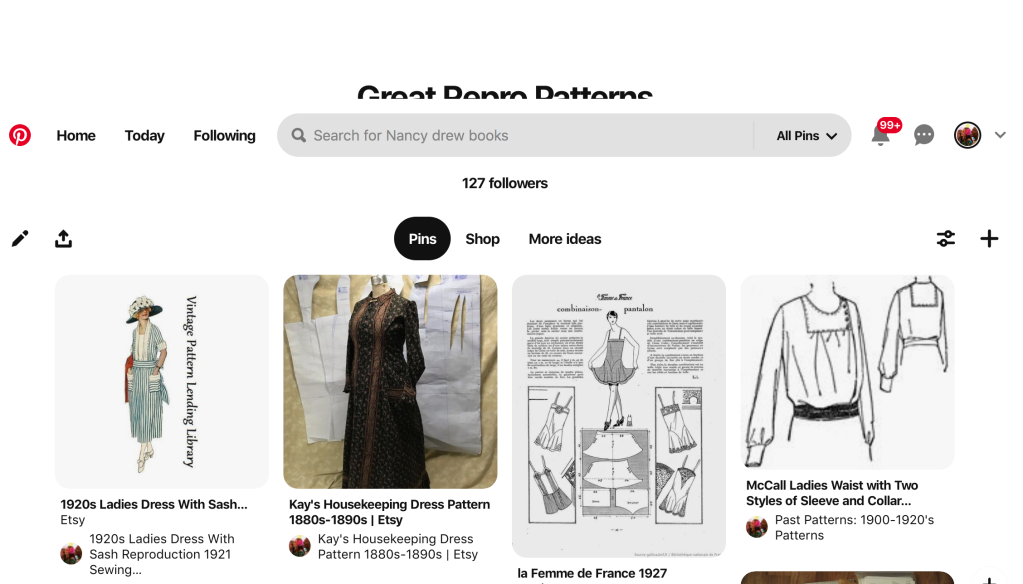

One question Ayana asked was: Pinterest, Friend or Foe? Well, Pinterest is both! It is great for collecting images, or for visually bookmarking tutorials and patterns (see step 1 below). It gets much more tricky when you try to use it to search for something, but we’ll get to the tips and tricks of that in a later post.

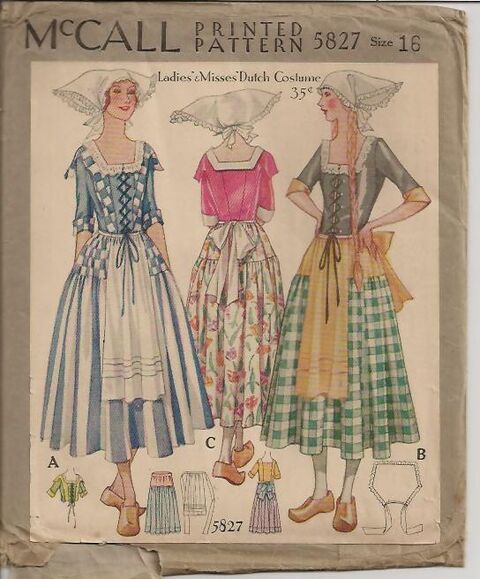

- I usually make a Pinterest board – yep, not academic in the least – of all the patterns available out there for the era in which I am interested. To take it back a step, I usually get interested in a particular era because of a book I am reading, or a podcast I have been listening to, or a movie, or a museum I have recently visited. However, I also prefer eras that are more “wearable” (aka comfortable!), like the regency period.

You might be surprised to find that I don’t always research a time period first, but this is:

a) because I am not a very skilled pattern drafter yet, so I prefer to work with already existing patterns, and

b) I actually find it easier to research once I have a more specific project in mind, rather than trying to learn ALL the things at once and getting overwhelmed trying to pick a dress style and then finding out there is no pattern for it. - Once I have a list of which patterns I think I will want to use, I do some searching on them, to see what others have used and if they had trouble with the patterns in any way:

a) I look at reviews on Pattern Review. There’s not a huge amount of historic costume activity there, though so next I check out…

b) Facebook/social media groups such as: The Historical Sew Fortnightly, Historical Pattern Reviews 1700-1920, 18th Century Stays – Research, Laughing Moon Sewing Pattern Support Group, 1730-1830 Clothing Construction Support Group

c) Some re-enactment and historic dance groups also have websites with recommendations for patterns. Unfortunately many are no longer updated or active. If you know of any active ones, please give us a link!

d) Sometimes I even just google something like “xyz pattern company #1000 blog review”. Lots of historic costumers used to have/still have blogs, because it is easier to write a long pattern review on a blog, with many photos, than on Instagram. If I am really desperate I will search hashtags on Instagram, but that is a last resort. - If one is making a certain type of garment they have never made before, or working in an era that is new to them, I suggest starting by using a kit, or modeling a project after someone else’s. Please give credit to them if you have done this when you post online about your project – don’t just take credit for the research they have done – and I would not suggest doing this for very unique projects, more for things like undergarments, which are less individualized. Some people do not like their more unique projects to be copied exactly.

- Once I have decided on my patterns, I usually take a trip to the library*, and gather as many books as I can find on the time period, especially if they are specific to costume. That way, as I go, I can either thumb through them in my free time for pleasure, or if I have a question I can start there. Usually my biggest questions revolve around what types of fabric were most appropriate, and how should the garments fit.

*Obviously, hitting up the library or used book stores is not always feasible during the pandemic.

One thought on “Sewing Historic Clothing Research: A Beginner’s Guide Part I”